A whistle stop history of the twentieth century in Gdansk

If you are a real history buff you will already know about Gdansk. Formerly known as Danzig, this unassuming city on Poland’s Baltic Coast has played host to many of the most momentous moments of the twentieth century.

Think back to news footage – the grainy reels showing soldiers going off to war, contrasted against propaganda recordings of Hitler’s masses. Mass strikes in the 1980s as workers exercised their rights to ask for better conditions. And who over a certain age can remember the incredible scenes as on 9 November 1989 the Berlin wall, iconic symbol of mass oppression, was finally torn down to allow families who had been separated for years to be reunited?

It would not be tenuous to say that many of these events had their origins in this Polish city. As the place where the first shots of WWII were fired and the birthplace of the Solidarity movement, happenings here sowed the seeds for movements that changed the world beyond recognition.

But don’t be fooled by this into thinking that only a real die hard history aficionado will find Gdansk’s phenomenal museums and sites of interest. As a family travelling with two young people, one of whom has a vocal dislike of museums, our long weekend to the city was jam packed full of fascinating history, presented in such a way as to appeal to every member of the family.

First stop on the agenda was the Polish Post Office. On 1 September 1939 German SS troops attacked the small post office in which around fifty postal workers were housed. Due to growing tensions between Germany and Poland in the preceding months, the post office which had another, more surreptitious, role as the centre of Polish intelligence gathering, had been identified as a potential target. The workers had been provided with weapons to enable them to resist any attack until reinforcements could be brought in. As it happened, no such help arrived, as the Germans had simultaneously launched its invasion of Poland and the troops were needed elsewhere. The postal workers put up a brave resistance for over seventeen hours, until part of the building collapsed, the Germans brought in flame throwers and they were forced to surrender. Almost all the survivors were summarily executed shortly after the siege.

Outside the Post Office is a large stainless steel monument erected in 1979 to commemorate the Poles who died during the siege. The Monument to the Defenders of the Polish Post Office is a striking representation of what has become one of the most feted examples of Polish heroism during WWII.

There is also a small museum housed inside the original building. Unfortunately, this is completely inaccessible to the wheelchair user as there is a steep flight of steps to get inside. We did ask the staff about this, who had the good grace to look slightly ashamed as they told us that the owner of the museum was not prepared to change anything, thinking disability access to be unimportant. I will refrain from comment.

Around the back of the building is a very sobering memorial to the men, women and children who died. A long wall bears many plaques of fingerprints to represent those of the individuals who were summarily shot after the siege for fabricated crimes. The one for the child is particularly horrific when it is seen to not even be at shoulder height to my son. At the end of the wall is an arresting photograph adapted from one taken by one of the Nazi onlookers.

Both the memorials are easily accessible to wheelchair users and definitely serve to provide a harrowing insight into the events that happened here.

Around the corner from the Post Office is the absolutely phenomenal Museum of the Second World War. Housed in a striking and award winning angular building, the museum itself is underground with the above ground part of the building being dedicated to offices. No matter, access is impeccable, with two alternative entries. At the main entrance, one simply needs to ring a bell and then there is a wheelchair lift to get down. There is also a disabled entrance round to the side of the building and down a very long ramp. Once inside, there are no issues with accessibility with lifts to all floors and plenty of space to move around all of the exhibits. Allow yourself plenty of time however as the museum really is something and you will want to linger.

The museum documents the history from even before the war, charting the aftermath of WW1 and the rise of fascism peppered with many images of Hitler and Mussolini during their rise to power. It details the part Poland played in the war, especially in the early days before going on to look at the bigger picture as Hitler started to implement his ‘Final Solution’ and the concentration camps. It even goes on to talk of the Manhattan project as US scientists looked for ways to beat the opposing forces.

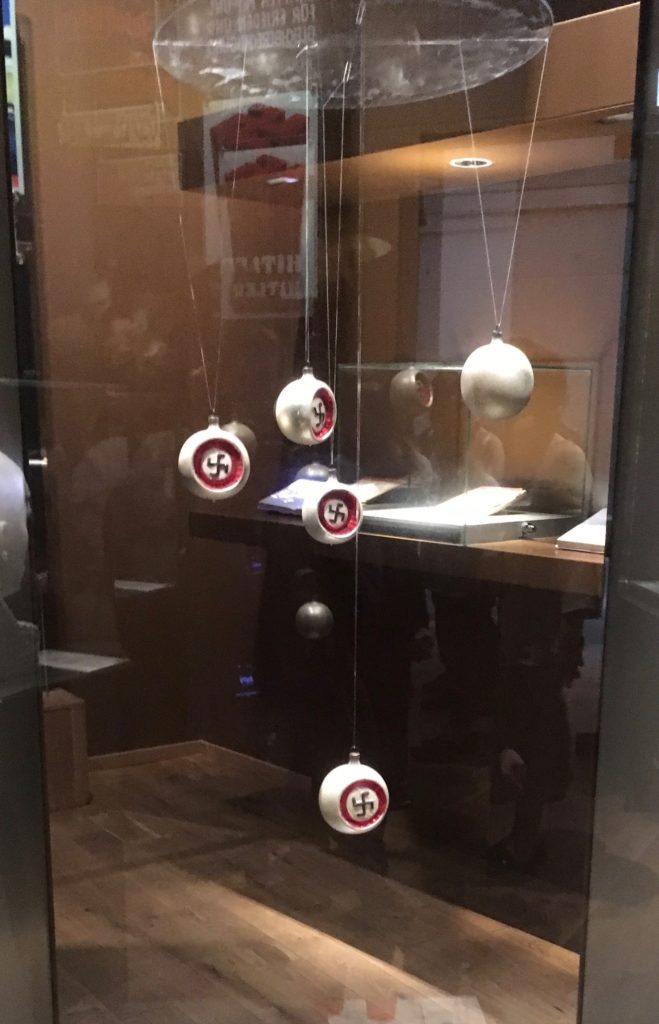

There are many incredible elements to this museum. There are plenty of fascinating exhibits such as the Swastika decorated Christmas baubles and the uniforms from the SA, the Nazi party’s original paramilitary.

There are pictures and footage aplenty, everything accompanied by explanation in English as well as Polish so there can be no doubt about what you are looking at.

For me personally, there were two things that really stood out above all the rest. Walk into one room and you will be greeted by the sound of Catholic masses being played while on a huge screen is illustrated the three million plus Soviet soldiers forced to starve to death as part of Hitler’s inhumane “Hunger plan’. This mass murder was an artificial famine, engineered by the Nazi party to ensure food supplies for its own army at the expense of the ‘racially inferior’ and ‘surplus’ Soviet population. Many of the victims were Soviet POW’S who were simply left to starve. I this room is some incredibly powerful footage, detailing the privations and torment these men had to endure.

Towards the end of the museum is another, equally harrowing, room housing walls of photos of some of the six million Jews exterminated as part of Hitler’s campaign. In terms of numbers, it displays only a snapshot yet serves as a sobering reminder that amongst the numbers often touted are individual men, women and children. Once again, it was the images of children that really resonated.

Day two

A slightly soggy day saw us on a pirate boat sailing along the Motlawa river towards Westerplatte, the site where the first shots of the war were fired. For anyone, wondering why a pirate ship, there are many boat trips organised along the route as the best way to get to the site. And why go on a normal boat when you can go on a pirate ship?!

Joking aside, access is achievable if you are happy to be lifted. The boat itself had a ramp and very willing, friendly staff, but there were steps to get down on the jetty. We were directed towards a ramp but it had the kind of gradient that makes occupational therapists go white with fear – I guess it would be OK if you fancied a dip in the river before your excursion!

For anyone for whom this would not be appealing, bus 106 from the main train station can take you to Westerplatte. While we did not personally use any of the buses whilst in Gdansk, the tourist office informed us that the greater majority are indeed wheelchair accessible and can be checked with the timetable.

Westerplatte is a strange place. It is quiet. Very quiet. There is a trail through the woods that documents some of the key features of the attack on 1 September 1939 when the German battleship Schleswig- Holstein let loose a barrage of artillery fire on the military depot stationed here and effectively started the war that had the most devastating impact of all wars before or since. It tells how the small garrison stationed here, aware of their vulnerability in the face of Hitler’s increasing aggression, fortified themselves as best as they could against the expected attack. Prevented from stationing many men there, due to stipulations in the Treaty of Versailles, in the end two hundred soldiers were able to repel the German forces, numbering over three thousand for more than a week. They showed phenomenal courage which was subsequently recognised by the German forces who allowed the Polish general Henryk Sucharski to keep his sabre in recognition of the valour of his forces.

There is a small and simple memorial dedicated to the fifteen men who lost their lives during the battle.

The ruined army guardhouse clearly shows the severity of the attack on Westerplatte. It has been equipped with a ramp so that one can get inside and view the remains.

Further along is a huge concrete monument entitled “Monument to the Defenders of the Coast’. Built of 236 granite blocks it was unveiled in 1966 and has since become the site for annual memorial services relating to WWII.

There is a pathway up to the monument but this is not accessible by wheelchair users. However, its huge size means that one can still get an excellent feel for it from the base and should not put anyone off visiting. The site as a whole is pretty accessible. The initial path is slightly uneven but on fairly solid ground so should be manageable for most people. Once out of the woods, the route is nearly all concrete so presents little difficulty, with occasional ramps interspersed with any steps. There is not much to see on past the monument and indeed the accessible route does run out shortly afterwards. All in all, it is definitely worth a visit and shouldn’t present too many obstacles for the wheelchair user.

Day three

I want to start today by making a point. Our family are very divided on the subject of history. My husband is a history fanatic and loves nothing better than to spend his time watching old documentaries about the war, especially if they contain lots of references to Spitfires. Molly – history is not her thing. Stan has an absolute passion for ancient history and can talk with authority beyond his years on anything to do with Greek mythology. As the charming American man at the British Museum found out when he tried to tell Stan something about one of the Greek exhibits and was quickly and accurately corrected…. He has also watched the entire series of ‘Horrible Histories’ at least five times and is often my go to when I have forgotten some fact or other. I have what I consider to be a normal and healthy interest in the events of yesteryear.

Overall, I would consider us to be a fairly accurate representation of many families with teens / almost teens and as earlier posts have indicated, a largely historical itinerary is not often suggested in lists of how to keep teens happy on holiday. So one may expect that following such a plan may have caused a few cracks in our family harmony by day three, especially when more of the same was proposed. But surprisingly enough this was not the case. I would suggest that this is reflective of the sheer impact of the museums and sites we visited while in Gdansk and this was definitely the case at the Gdansk shipyards and European Solidarity Centre we visited on our final day.

As a child of the seventies I grew up familiar with strikes on the news as workers fought for better conditions and pay. I can vividly remember the imagery of the miners strikes and Maggie Thatcher in her bright blue dresses as she did verbal combat with Arthur Scargill. This dominated our TV screens and newspapers for months and came to be a powerful reminder of the era. But prior to that in a small town on the Baltic coast, a different workers movement was starting which, against all the odds, was to be the catalyst that led to the eventual fall of the Soviet Union.

In the 1970’s shipyard workers in Gdansk were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with plummeting living conditions and this sparked a series of protests which resulted in a number of deaths. While initially quelled by the authorities, tensions still simmered under the surface and the dismissal of a female crane operative, Anna Walentynowicz, on 7 August 1980 led to a young man called Lech Walesa to scale the wall of the shipyards and call for a strike. An abridged version of the story results in a momentous albeit temporary victory against the Communist authorities with the signing of the August Accords and the birth of the Solidarity movement or ‘Solidarnosc’ as it is called in Polish. The movement experienced many ups and downs over the intervening years but its role in the eventual breakdown of the Communist regime in Eastern Europe cannot be undermined.

Visitors to the shipyards are first confronted with the towering ‘Monument to the Fallen Shipyard Workers of 1970’. This monument was unveiled in 1980 and was to commemorate the forty five people who died during the clashes with the communist forces. It has a dual impact – whilst it commemorates a tragedy it was also one of the chief demands made by the workers during the August Accords and as such represents a hard fought victory. Concentric circles of cobbles make getting very close to it a bit bone shaking but at forty two meters tall it is not necessary to approach too closely.

On the far side of the monument is the entrance to the shipyards and visitors can go through the iconic gate where Lech Walensa addressed the masses and get a real feel for what the shipyards would have been like. Once again, the ground is flat and access is easy.

The whole site however is dominated by the imposing building which houses the European Solidarity Centre. Built to resemble a ship under construction, the outside is clad in huge plate of rusty metal but it is inside it really comes into its own. The ground floor houses a large atrium filled with plants and comfortable seating areas where one can sit and view the impressive design of the building. Completely accessible with lifts to all floors, hard flooring throughout and plenty of space to manoeuvre this chronicle of the birth of the Solidarity movement grabs you from the outset as the first door takes you into a room with tens of yellow helmets fixed to the ceiling to represent the shipyard workers. From there visitors are treated to a fascinating journey through the key events in the Solidarity movement s history and beyond, as its impact on the future world is assessed. This is done through a combination of footage, images, artefacts and interactive displays. Audio guides are available and highly recommended as they come equipped with sensors that identify where in the displays you are and tailor their narrative accordingly.

One of my own personal favourites was the huge Solidarity logo made up entirely of hundreds of notes on which visitors had written their own thoughts.

A lift to the top floor enables access to a roof terrace which affords a panoramic view over Gdansk including the cranes which still dominate the skyline today.

My only regret – we did this on our last morning and didn’t allow enough time.

Our trip to Gdansk was perhaps not the conventional first choice for a family with two (almost) teens to make. Add that into the mix the extra complications involved in going to a city full of cobbles and steps when one or more of the party is a wheelchair user and one may ask why?!

I can honestly say that our trip to Gdansk was fantastic, a view shared by all members of the family, despite their differing interests. The places we visited were hugely interesting and presented in such a compelling visual and interactive way as to appeal to all of us. Coupled with the mostly achievable access, at least to the main sites, this is a trip that should appeal to young and old, history fans and otherwise, whether able bodied or not.